Reviewed by Harriet

It has always been my intention to practice the arts of pretence and counterfeit on the reader.

So wrote Muriel Spark in an unpublished Author’s Note to The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. When I saw that this new biography was soon going to be published, I knew I had to read it. For one thing I’m a great admirer of Frances Wilson’s excellent biographies, two of which I’ve reviewed on here, so I knew this would be a fascinating read. And for another, I had a great splurge on Muriel Spark’s novels back in 2010, and in 2012 I co-hosted Muriel Spark Week on my blog. That blog is now defunct but still available online, so if you’re curious enough you can still see some of my reviews. I read quite a bit of Spark during that period, but my favourites, in addition to The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, were Loitering With Intent, The Girls of Slender Means and A Far Cry from Kensington. In every case I loved the quirkiness, the strangeness of the characters, and the postmodern freedom of the structures and events. I also felt sure that some elements of them all must have been autobiographical. Only now, after all this time, do I realise how everything in the novels can be related back to Spark’s extraordinary psyche and the effect it had on those who loved her or hated her, often simultaneously.

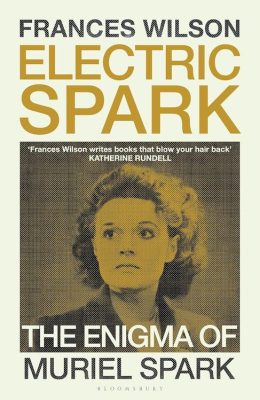

There have of course been other biographies, most notably that of Martin Stannard, which Spark agreed to initially but blocked from publication when she read it, calling it ‘a hatchet job; full of insults…slander [and] defamation’. The book finally came out in 2009, three years after her death, and the edition I’m looking at has a quote on the front from Frances Wilson: ‘Gripping…about as satisfying as a literary biography can be’. Writing in the preface of the current book, sixteen years later, Wilson says ‘Electric Spark is not a revision of Martin Stannard’s biography, nor can I pretend it is the biography Spark wanted all along or even, strictly, a biography’. Electric Spark does not cover Spark’s later years of success and acclaim, not does it analyse any of the novels in any great depth, and only when they shed light on Spark herself; instead, it spends most of its 432 pages on ‘the years of turbulence’ when she first arrived in London from Rhodesia in her mid-twenties, having left her mentally ill husband and her small son behind. It would be over twenty years until her first novel, The Comforters was published, though she had published poetry, critical editions, a biography of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, and three volumes of collected letters (the Brontës, John Henry Newman, and Mary Shelley). But these facts in no way encompass the extraordinary range of Wilson’s book, which is really a psychological study of one of the most strange and bewildering minds you could ever hope to meet or even imagine. The description of her early years are of a life in which ‘everything was piled on: divorce, madness, murder, espionage, poverty, skullduggery, blackmail, love affairs, revenge and a major religious conversion’. She hoarded every bit of paper with any relevance to her life and to her work, which were divided and donated to two separate universities. The number of box files containing her archive were ‘equivalent in height to an airport control tower, in length to an Olympic sized swimming pool, and in width the wingspan of a Boeing 777’. She believed that ghosts existed, and that authors would return to tamper with their own books. She had a mental breakdown, partly brought on by taking large quantities of diet pills, and became severely paranoid, believing at one time that T S Eliot was stealing her baked beans. She laid clues in her writing for future readers and biographers to solve. Where in all this, Wilson asks, is her hidden self?

I came away from all this with enormous respect and admiration for Frances Wilson, and am honestly surprised that she managed to retain her sanity researching this book: she said in a recent interview that ‘I wasn’t immersed by her. I felt actually possessed by her’, something she believes a lot of her friends and lovers also experienced. I suppose I also came away with respect and admiration for Spark herself, but I’m glad I never had to be one of her friends, as almost all of them suffered from her acquaintance in various ways. This was an amazing read and will probably win many well-deserved prizes.

Harriet is a co-founder and one of the editors of Shiny.

Frances Wilson, Electric Spark: The Enigma of Muriel Spark (Bloomsbury Circus, 2025). 978-1526663030, 432pp., hardback.

BUY at Blackwell’s via our affiliate link.

Thanks Harriet – this sounds amazing!!