Review by Annabel

Lindsey Fitzharris is an American with a doctorate from Oxford in the History of Science, Medicine and Technology, and a post-doc fellowship from the Wellcome Trust. Her first book, published in 2017 and later shortlisted for the Wellcome Prize was The Butchering Art, subtitled ‘Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine.’ This book portrayed the world of Victorian surgery in the late middle of the 19th century, and it was a world of speed amputations, in which, if you were lucky enough to survive the surgery, you were likely to die of sepsis or gangrene afterwards. Enter Quaker doctor Lister who, after many battles, introduced antiseptic techniques which led to so many advances in hospital medicine.

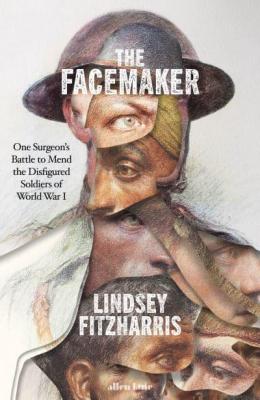

Fitzharris’ second book moves on to the horrors of the First World War, and the work of Harold Gillies, one of the first facial reconstruction surgeons, but not without a reference back to Lister first.

Ironically, the surgeon Joseph Lister—who is credited with saving tens of thousands of lives in the nineteenth century by introducing antiseptic techniques to the practice of surgery—was indirectly responsible for the high incidence of sepsis in Europe at the start of the First World War. His success meant that the latest generation of surgeons, brought up on germ theory and treating principles of asepsis, were unaccustomed to identifying and treating infected wounds, since they rarely encountered them in their day-to-day practice. But the rich farming soil of France and Belgium harbored lethal microbes that caused tetanus, gas-gangrene, and septicaemia. […] A surgeon quite literally sealed a soldier’s fate when he sutured a wound packed with bacteria.

The book begins in 1917, by telling the story of one of Gillies’ patients, Private Percy Clare, who was in a trench at Cambrai, waiting to go over the top When he does, and a bullet tore through his cheeks, he was lucky to survive. Firstly, stretcher orderlies routinely ignored those with maimed faces, but his friend found him and arranged his removal from the killing field. Secondly, he didn’t lie on his back, where he would have suffocated on his own blood, and later in the field hospital, that rarity at the front, a dental surgeon, decided to send him back to ‘Old Blighty’ and the new hospital in Sidcup, west of London, where Harold Gillies plied his surgical speciality. Clare was one of the lucky ones, he got there alive, and survived.

After this grim opening, (although there is plenty more grim to come), Fitzharris takes us back to 1913 to introduce the young up and coming surgeon, Harold Gillies, from Dunedin in New Zealand. He’d finished his clinical studies at Barts and was looking around for a specialty, thinking that Ear, Nose and Throat, ENT, might be interesting, when he landed a job working for a Sir Milsom Rees, a doctor in private practice looking after the throats of opera singers amongst others. Surprisingly, it was not Gillies’ prowess as a potential surgeon that got him the job, it was his hobby – for Gillies was a talented golfer and was making his way in the English Amateur Championships – Rees was keen to share his own swing. Gillies got the cushy job!

After the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, and the start of the War, Gillies wasn’t slow in signing up for the Red Cross, being called up in early 1915 to go to France, leaving his pregnant wife behind in London. It was at one of the field hospitals, that Gillies would meet the French dentist, Auguste Valadier, who wasn’t allowed to operate without a surgeon’s supervision.

As an ENT specialist with a deep understanding of head and neck anatomy, Gillies was uniquely qualified for the job. But it was arguably Gillies who benefitted most from this early partnership. Not only did it teach him the value of dentistry to the practice of facial reconstruction, it also demonstrated to him the transformative power of plastic surgery.

This was the first of many collaborations for Gillies. Yes, he was ambitious and hard-working, but he recognised the value of teamwork, and as his career developed, he surrounded himself with similar-thinking medics. He and his teams were responsible for developing many new techniques in plastic surgery, although there was often rivalry from other plastic surgeons around the world as to who developed which technique first. We learn all about ‘tubed pedicles’ and ‘epithelial lays’, both specialised techniques for maintaining blood supplies to skin grafts while they take.

In between the stories of Gillies’ work at the Queen’s hospital, Sidcup, and discussing the history and development of plastic surgery, we catch up with Private Clare. In a certain way, Gillies’ patients were victims of his success, for they were running out of men at the front, and in January 1918, Private Clare was recalled.

One thing that Gillies did was to document his procedures, and the photo section shows a selection of before, during and after operations on some survivors, which are both alarming and comforting. Fitzharris debated whether to include them, but I agree they are necessary to the book. The injuries are terrible to look at, the ongoing treatment needed and myriad of operations over a period of months or years show how gruelling it was for these poor men. Yet there is some comfort to be found as in many cases, Gillies and his teams were able to rebuild missing jaws from rib bone and skin grafts for instance, allowing the patient to eat again. Of course, they didn’t always succeed, and there are also sad stories of those who couldn’t cope with their changed appearance.

Although most of the book is concerned with the surgeons’ work during and immediately after WWI, Fitzharris closes it by sharing what Gillies did next. He moved into private practice, one of his patients known as ‘Big Bob’ being his secretary. Some accused him of selling out, but he continued to push the boundaries of plastic surgery until he died shortly after suffering a stroke at the operating table – he was seventy-eight.

As in her previous book, Fitzharris offers an effective blend of biography and the history of medicine together with the stories of the horrors of the war. She doesn’t shy away from the gore, for it is what gave Gillies his raison d’être and humane desire to help to rebuild lives. The Facemaker is compelling reading and I recommend it.

Annabel is a co-founder and editor of Shiny. She loves getting to grips with surgical history!

Lindsey Fitzharris, The Facemaker (Allen Lane, 2022). 978-0241389379, hardback, 343 pp. incl plates.

BUY at Blackwell’s via our affiliate link (free UK P&P)

Sounds inspiring, if grim, Annabel. What a terrible conflict it was and how wonderful those pioneering surgeons were.