Review by Rob Spence

It probably doesn’t occur to many people as they struggle to fix bolt B to batten F of the Ikea flatpack wardrobe that the exercise in which they are engaged had its genesis a century ago in the vision of Walter Gropius, whose commitment to well-designed houses and furniture for the masses produced the astonishing flowering of talent that was the Bauhaus, and whose influence lasts to this day. We are, as this book demonstrates, indebted to Gropius and his fellow Bauhaüsler for many of the most recognisable design classics of the modern era, as well as fundamental changes in the way that housing, and indeed whole cities are organised.

2019 marks the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the Bauhaus in Weimar, and also the 50th anniversary of Gropius’s death. This has given rise, predictably, to a spike in the publication of books about the Bauhaus and its originator. Fiona MacCarthy’s splendid biography is the most substantial of the ones I have seen, concentrating firmly on the figure of Walter Gropius, architect, designer and visionary. Rather amazingly, given the fact that her subject died in 1969, Fiona MacCarthy met Gropius when she was, as she puts it, “a mini-skirted Courrèges-booted young journalist” in 1964 at the London relaunch of the Isokon Long Chair, designed by Bauhaus alumnus Marcel Breuer. It sparked an interest that led ultimately to this meticulously researched biography, one which will surely establish itself as the standard work. Fiona MacCarthy is animated by a desire to re-evaluate not just Gropius’s achievements, but also his image: she wanted to counteract the received wisdom that Gropius was a rather humourless ascetic type, and to present a fully-rounded picture of a remarkable man. In that, she has succeeded handsomely.

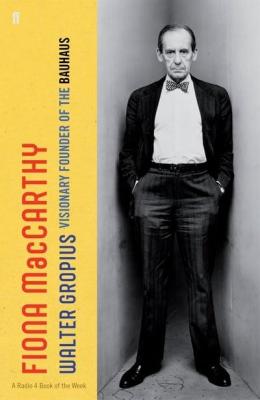

That rather forbidding image of Gropius, the one he was saddled with in later life, is perhaps illustrated best by the image on the dust-jacket. Gropius, aged 64 in a dark suit and his signature bow-tie, scowls somewhat at the camera from a dark corner of some concrete edifice. He might be a stern classics professor, perhaps, with, one might guess, little time for his students. MacCarthy’s biography triumphantly gives the lie to that impression, and establishes from the start that Gropius was a man of intense passions, an inspiration to other artists, with an unwavering commitment to his aesthetic ideals.

MacCarthy deals briskly with the childhood, and we are not far into the volume before Gropius is established in the Berlin office of architect Peter Behrens, working at one time alongside Mies Van der Rohe. Before long he is working for himself, and is responsible for a major building, the Fagus factory at Alfeld-an-der-Leine, completed in 1914. This building’s confident modernity, with its extensive use of glass giving it an airy lightness, must have astonished contemporary observers. Indeed, MacCarthy reports that occupying American troops after the Second World war had to be shown the original plans in order to be convinced that the building was in fact at that point more than thirty years old.

Two major events at this point in the life of the budding architect occur around this time: his meeting with the volatile Alma Mahler, wife of the composer, and the outbreak of the First World War. Gropius’s relationship with Alma was an intensely passionate one, its repercussions lasting for the rest of their lives. Commencing before the death of the much older Mahler, the affair ebbed and flowed in a tide of passion and self-disgust, evidenced by some startlingly intimate letters. Alma’s dramatic self-importance was based around an ability to inspire absolute devotion among her admirers. The battle for her affections between Gropius and the artist Oskar Kokoschka is an extraordinary tale, featuring at one point a life-sized doll of Alma. By the end of the war, during which Gropius and Alma had married, and she had given birth to their tragically short-lived daughter, the relationship had foundered, and Alma was pregnant by her new lover, the poet Franz Werfel. The war, too, was a shattering personal experience for Gropius, a brave officer in the Hussars, who saw action more or less continuously for the extent of hostilities, receiving the Iron Cross early in the conflict, and suffering several serious injuries.

The opportunity to build and lead a new school of art and design in Weimar was irresistible to Gropius, and in 1919 he began his tenure as the director of the Bauhaus. MacCarthy rightly pays great attention to this period, detailing both the artistic advances associated with the institution, and the personal changes in the life of Gropius. The Bauhaus was, in the circumstances, an astonishing achievement. First at Weimar, and then at Dessau, Gropius shaped a new vision of art and design education, coping with the perilous state of post-war Germany, and developing his vision of the Gesamtkunstwerk, where different arts and crafts would combine to produce the final object. The Bauhaus concept owed something to the English Arts and Crafts movement associated with William Morris and C.R. Ashbee, but always, with Gropius, geared to contemporary machine production. MacCarthy’s account of the Bauhaus years is particularly rich, and brings out the sheer explosive creative energy of the period, as Gropius assembled a team of artist-practitioners who would become major forces in their fields: Paul Klee, Joseph and Anni Albers, Marcel Breuer, László Moholy-Nagy, Johannes Itten, Wassily Kandinsky. These “Masters” as they were called inspired their students in a daring atmosphere where social and sexual relationships were as modern as the art. Gropius’s own hectic romantic life settles here, with Ise, his second wife providing stability.

Despite his growing stature, Gropius struggled to get the necessary backing to complete major projects, and the advent of the Nazis was the last straw. Leaving for Britain, he was welcomed by Jack Pritchard, entrepreneur and patron, whose Isokon flats in Hampstead provided a haven for Gropius and a whole group of exiled modernists, including some from the Bauhaus. This was really an interlude, however, before Gropius accepted the offer of a prestigious post at Harvard in 1937, where he worked for the next fifteen years, retiring as a grand old man of architecture, still possessed of a restless energy and an unquenchable enthusiasm for work that would articulate his vision. MacCarthy covers this period sensitively, detailing the highs and lows, and revealing a man at pains to preserve his legacy, but still committed to innovative and exciting design.

The final years show no diminution of the desire to engage with new ideas and explore new opportunities. Gropius travels far and wide, in Japan, Brazil, Iran, Australia, ever inventive, ever implementing his vision. Even though many of Gropius’s most radical ideas never reached fruition, he left an impressive portfolio of achievements, from large factory and educational buildings – notably the Bauhaus building itself, of course – to single houses and housing schemes, not to mention furniture, cars, porcelain and other household items. MacCarthy quotes with approval Neil MacGregor’s summation of the influence of the Bauhaus: “The Bauhaus reshaped the world. Our cities and houses today, our furniture and typography are unthinkable without the functional elegance pioneered by Gropius and the Bauhaus.”

Fiona MacCarthy set off with a didactic purpose in this biography, to present a portrait of Gropius that readjusted the received wisdom on his character and influence. I think she manages to do so, by means of a thoroughly researched account of what is, by any standards, a remarkable life. She is very sympathetic to her subject, but not at all uncritical: his failings are scrupulously held up to the light. In the end, she notes that his genius was not so much as an architect, but as a central point around which other forces could coalesce. His talent, he said, “is for seeing the relationship of things.”

This book should be required reading for anyone with an interest in twentieth-century architecture and design. It is beautifully produced, with colour plates and copious black-and-white illustrations, a comprehensive reference section and a very useful index. She has done Gropius proud, and produced a volume that invests him with the humanity previous attempts have lacked.

Rob Spence’s home on the web is robspence.org.uk or find him on Twitter @spencro

Fiona MacCarthy, Walter Gropius: Visionary Founder of the Bauhaus (Faber, 2019) ISBN: 9780571295135, 547pp, hardback

BUY at Blackwell’s via our affiliate link (free UK P&P)