Translated by Ruth Martin

Reviewed by Harriet

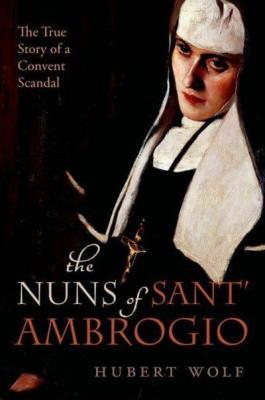

This is certainly an extraordinary and fascinating book. Written by a celebrated German papal historian, it manages to combine highly academic ecclesiastical history with true crime and more than a smattering of frank sexual revelations. But the story it tells is a shocking and ultimately tragic one, though perhaps not in the way you might think.

The story starts in 1859, when a devout German princess managed to smuggle a letter out of the convent of Sant’ Ambrogio della Massima in Rome. Katharina von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen had entered the convent voluntarily just over a year earlier – having been twice widowed, she was happily fulfilling her life-long desire to become a nun. But she had learned dangerous secrets, which led to her being ill-treated and isolated, and finally, several attempts had been made to poison her. Fortunately the letter reached her cousin, an Archbishop in the Vatican, who believed her story and secured her release. Katharina presented a report to the Inquisition, and as a result a scandal broke, one of such epic proportions that the details were suppressed for nearly 150 years.

The convent had been founded in 1806, and Maria Agnese Firrao, a nun reputed to have extraordinary spiritual visions, became its first abbess. But a few years later she was investigated, found guilty of ‘feigned holiness’, and sentenced to life imprisonment. An attempt was made to close the convent, but it succeeded in staying open, though its inmates were forbidden to venerate Firrao as a saint. However, as Katharina discovered, the cult of Firrao continued to flourish within the convent walls: the nuns prayed to her and treated her surviving texts as holy relics. What’s more, certain practices she had introduced were continuing to be carried out by the current vicaress of the convent, Madre Vicaria Maria Luisa. When she was called before the Inquisition, the facts that came to light were so shocking and unprecedented that they threw the inquisitors into a state of great confusion.

Maria Luisa had been thirteen when she entered the convent. Possessed of great beauty and charisma, she was believed from the start to be ‘a soul particularly favoured by God’. By her early twenties she had attained her high position on the strength of her frequent visions and mystical fits. She exuded a divine fragrance of roses, and wore a large and valuable ring said to have been given to her by the Virgin Mary, who soon began to write letters to her, which materialised in a small wooden casket to which only the convent’s confessor, Padre Peters, had the key. The nuns, mostly young women from quite humble backgrounds, had no trouble in accepting all this. Or most of them did not. A few of them had witnessed, or been involved in, numerous ‘immodest acts’ carried out by Maria Luisa with other nuns, act which she claimed had been part of the Virgin Mary’s instructions. Furthermore, one or two had become suspicious of the long hours that Padre Peters often spent locked in Maria Luisa’s cell.

The truth finally emerged in a series of sessions within the inquisition. Several nuns were called as witnesses, and described in detail their seduction by Maria Luisa into numerous lesbian activities, which they had been told were essential for their spiritual development. Finally the vicaress herself stood before the inquisitors and told her own story. She herself had been seduced at the age of thirteen by the then Mother Superior, who was carrying on a tradition that had begun at the time of the convent’s foundation, initiated by the first abbess, Maria Agnese Firrao. Maria Luisa’s confession was very full and very frank. She freely admitted not only the lesbian acts, but also her sexual relations with Padre Peters and her ‘feigned holiness’, including the forging of the letters of the Virgin, and her acquisition of the ring and the rose oil used for the divine fragrance. And to cap it all, she admitted to the murder of several nuns.

If all this was not bad enough, another shock was in store. Padre Peters, the humble and holy confessor of the convent, proved to be none other than the much respected Jesuit author and theologian Joseph Kleutgen. He too was forced to confess his sexual misdeeds, including an intense sexual relationship with a young woman outside the convent. He tried to make the best of it, claiming that ‘during these acts I never ceased my inner prayer’, but that did not prevent the inquisitors from finding him guilty.

So what happened to the two main players in this sad and sorry story? Well, after much debate and many internal disagreements, the inquisition sentenced Joseph Kleutgen to five years’ imprisonment and banned him from taking confession from both men and women. However, his sentence was soon reduced to three years and then finally to just two. Although his reputation was initially damaged, he managed in the end to be fully reinstated, and his subsequent biographers made no mention of the Sant’ Ambrogio affair. Maria Luisa was not so lucky. Initially sentenced to eighteen years in prison, she shuttled between there and a mental asylum, with brief periods at home with her family, who quickly found they could not cope with her bizarre behaviour. Under the circumstances, her loss of reason is hardly surprising, and even though she was finally freed, she vanished from history and what happened to her in her final days remains unknown.

This remarkable story is told in great detail by Hubert Wolf, and the book contains an impressive bibliography and many pages of notes. The fact that he was able to write it at all is owing to the fact that the papal archives were made accessible to researchers for the first time in 1998. Prior to that, despite some incomplete accounts in the Italian press at the time of the scandal, the whole affair had been comprehensively suppressed for more than a hundred years, and Kleutgen had remained a figure of high and apparently unsullied reputation. To read it now, in the light of the current revelations of child abuse, sheds an interesting light on it all. As Wolf himself points out, Maria Luisa was a victim of abuse, one who, as is often the case, went on to perpetrate what had been done to her as a child. Add to that the fact that the church imposed the strictest celibacy on men and women who were, in the final analysis, only human beings who were attempting, with no doubt the best motives in the world, to suppress their natural desires, and you have a volatile mixture which was guaranteed to explode. This is in no way to exonerate the people involved, but I think some understanding is called for in what is ultimately a sad and tragic history.

Harriet Devine is one of the editors of Shiny New Books.

Hubert Wolf, The Nuns of Sant’ Ambrogio: The True Story of a Convent Scandal, translated by Ruth Martin (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2015). 9780198732198, 496 pp., hardback.

BUY at affiliate links: Bookshop.org or Blackwell’s.