Translated by Lytton Smith

Review by Peter Reason

This book focuses on two things that are changing beyond recognition in this era of rapid ecological change: Time and Water.

Time has taken on a mythic dimension: human history and geological history have converged as ‘Earth’s mightiest forces have forsaken geological time and now change on a human scale… Changes that previously took a hundred thousand years now happen in one hundred’.

Over the next 100 years, glaciers will melt away, ocean levels will rise while at the same time as acidification will increase; there will be droughts and floods. ‘All these things will happen during the lifetime of a child born today.’ (Of course, all this is already happening.)

These changes surpass any of our previous experiences, surpass most of the language and metaphors we use to navigate our reality. ‘Climate change’, ‘ocean acidification’ and all the rest are words we quite simply ‘do not understand’. While they should strike terror in our hearts, they are ‘like white noise… It’s as if the brain cannot register changes on such a scale’. Magnason suggests it is it better to think of climate change like a black hole: ‘The way to detect black holes is to look past them, to look at nearby nebulae and stars.’ The only way to write about climate change is ‘to go past it, to the side, below it, into the past and into the future, to be personal and also scientific and use mythological language…’ As I read this, I am reminded of Emily Dickinson, ‘Tell all the truth, but tell it slant…’: the truth, Dickinson implies, is too overwhelming for us to be able to cope with in one go.

I learned about On Time and Water when Twitter led me to an interview in Emergence Magazine, and I asked for a review copy thinking Magnason’s approach worth looking into. There have been so many attempts to speak about climate change, going right back to Dennis and Donella Meadow’s Limits to Growth in 1972, to James Hansen’s testimony to the UK Congress in 1988, to Bill McKibben’s End of Nature in 2003, Clive Hamilton’s 2017 Defiant Earth, David Wallace-Wells’ 2019 The Uninhabitable Earth, Alastair McIntosh 1920 Riders on the Storm. Maybe, I thought, Magnason was taking a new approach that would be constructive. Certainly, he takes an unusual slant: he moves between personal memory, travel writing, mythology, and science. In order to bring about a planetary paradigm shift, he says, we need new ways to see and imagine ourselves into the future.

There are points in the book where I felt truly touched. He plays a game with his ten-year-old daughter while sitting in her ninety-four-year-old great-grandmother’s kitchen. He asks her to calculate the time between great-grandmother’s birth and the birth of her own imaginary future great-granddaughter—the potential span of people she might know, love, and touch in her life: the answer comes to 262 years. He tells his daughter, ‘You can touch 262 years with your bare hands. Your grandmother taught you, you will teach your great-granddaughter’. It’s a compelling thought. (I have done the same calculation for myself, between my grandmother’s birth in 1874 and my youngest grandchild’s potential 80 years, and the total comes to 226).

Later, he writes about watching old home movies of his grandparent’s participation in the expeditions to the Vatnajökull glacier with the Icelandic Geological Society, from immediately after their wedding in 1956 into the 1970s. These were pioneering expeditions into territory previously unexplored and unnamed by humans, with primitive equipment (by today’s standards), traversing ice that is 1000 meters thick in places. Today, the glacier is retreating at a rate unimaginable in the 1950s and 1970s: if his daughter lives as long as her grandmother, much of the glacier will have disappeared within her lifetime; where her great grandparents once camped will be up in the clouds. Magnason wrote the memorial of the Okjökull glacier, the first of hundreds that Iceland is expected to lose over the next 200 years. And he reminds us, it is not only Icelandic glaciers are dying; the Tibetan plateau, from which many of the Himalayan glaciers originate, like the Arctic, is warming much faster than the rest of the planet. These glaciers feed great rivers that bring life to the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent, which are also dying at an alarming rate.

I think Magnason is onto something in creating poetic narratives that make the geological personal in this manner: referring back to our living ancestors’ experience confronts the shifting baseline from which we experience the changing world; and it draws on our imagination in ways that statistics don’t—as he writes toward the end of the book, ‘A large part of the solution lies buried in our imaginations’. Of course, he not alone in working with time in this way: the ancient Haudenosaunee philosophy asserted that the decisions we make today should be mindful of their impact on seven generations into the future; poet Drew Dellinger’s powerful Hieroglyphic Stairway begins with the lines ‘it’s 3:23 in the morning/and I’m awake/because my great great grandchildren/won’t let me sleep…’

Time and Water has a lot to recommend about it. However, my feeling is that in the second half, the book loses its way somewhat. He pursues a poetic link between Audhumla, the sacred cow from the origins on the world in Icelandic mythology, and Mount Kailash, the sacred mountain of Hindu, Buddhist and traditions, and explores this in interviews the Dalai Lama. This is a theme which I find less than convincing but may well appeal to other readers. The later chapters don’t, for me, have the personal narrative edge of the earlier ones in which Magnason links climate change directly to his family history. Another drawback of the book for British readers is that we do not have the same cultural references to glaciers and Norse myths as do the Icelanders for whom the book was originally written.

There are many authors trying to get to grips with climate change through the written word. Some confront it head on with statistics, some with metaphor and poetics, others through the emerging field of climate fiction. As I reflected on Magnason’s book, the much-quoted phrase from Samuel Beckett’s Worstword Ho came to my mind, ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ This as been adopted as an inspirational slogan by technocrats of Silicon Valley, which is arguably a misreading of Beckett. In a Guardian article, literary critic Chris Power suggests Beckett came to believe failure was an essential part of any artist’s work, even as it remained their responsibility to try to succeed. Maybe we should take the quote as reflecting Beckett’s lack of faith in language, and the absurdity of using words to address climate change. Philosopher Tim Morton describes climate change as a hyperobject, an entity ‘of such vast temporal and spatial dimensions that they defeat traditional ideas about what a thing is in the first place’. He writes, ‘hyperobjects are funny. On the one hand, we have all this incredible data about them. On the other hand, we can’t experience them directly’.

Magnason’s attempt to look at time and water, at climate change, ‘slant’, to grasp it by looking past it, using personal narrative, myth and poetics, seems to me to be a really worthwhile ‘fail better’. It will not always work for everyone and can never encompass the whole terror we might, maybe should, experience. But the attempt, the imaginative exploration, is in itself deeply worthwhile.

Peter Reason is a writer who links the tradition of travel and nature writing with the ecological predicament of our time. He writes regularly for Resurgence & Ecologist, and has contributed to EarthLines, GreenSpirit, Zoomorphic, LossLit, The Island Review, and The Clearing. He has written two books of ecological pilgrimage, In Search of Grace (Earth Books, 2017)and Spindrift (Jessica Kingsley, 2014). With artist Sarah Gillespie he published On Presence: Essays | Drawings in 2019, following this in January 2021 with On Sentience: Essays | Drawings, both available directly from the author/artist. Find Peter at peterreason.net, and on Twitter @peterreason.

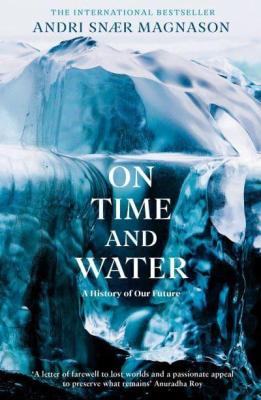

Andri Snær Magnason, On Time and Water (Serpent’s Tail, 2021). 978-1788165532, 352pp., paperback.

BUY at Blackwell’s via our affiliate link (free UK P&P)

1 comment

Comments are closed.